How To Set Up A Conventional Plough

Traditional ploughing: a farmer works the country with horses and turn

A plough or plow (US; both ) is a subcontract tool for loosening or turning the soil earlier sowing seed or planting.[1] Ploughs were traditionally fatigued by oxen and horses, merely in modern farms are drawn by tractors. A turn may accept a wooden, iron or steel frame, with a blade attached to cut and loosen the soil. It has been primal to farming for most of history.[2] The earliest ploughs had no wheels; such a plough was known to the Romans as an aratrum. Celtic peoples starting time came to utilize wheeled ploughs in the Roman era.[3]

The prime purpose of ploughing is to turn over the uppermost soil,[4] bringing fresh nutrients to the surface[5] while burial weeds and crop remains to disuse. Trenches cutting by the plough are called furrows. In modernistic use, a ploughed field is normally left to dry and and then harrowed earlier planting. Ploughing and cultivating soil evens the content of the upper 12 to 25 centimetres (v to 10 in) layer of soil, where nearly plant-feeder roots grow.

Ploughs were initially powered by humans, only the use of farm animals was considerably more than efficient. The earliest animals worked were oxen. Afterward, horses and mules were used in many areas. With the industrial revolution came the possibility of steam engines to pull ploughs. These in turn were superseded by internal-combustion-powered tractors in the early 20th century.

Utilise of the traditional plow has decreased in some areas threatened past soil damage and erosion. Used instead is shallower ploughing or other less-invasive conservation cultivation.

Etymology [edit]

Ploughing in Mysore, Bharat

In older English, as in other Germanic languages, the plough was traditionally known by other names, e.k. Old English sulh (modern dialectal sullow ), Old High German medela , geiza , huohilī(northward) , Old Norse arðr (Swedish årder ), and Gothic hōha , all presumably referring to the ard (scratch plough). The term turn, as used in the early on 21st century, was non common until 1700.[ citation needed ]

The modern word comes from the Old Norse plógr , and is therefore Germanic, simply it appears relatively belatedly (it is not attested in Gothic), and is thought to be a loan from one of the northward Italic languages. The High german cognate is "Pflug", the Dutch "ploeg" and the Swedish "plog". In many Slavic languages and in Romanian the word is "plug". Words with the same root appeared with related meanings: in Raetic plaumorati "wheeled heavy plough" (Pliny, Nat. Hist. 18, 172), and in Latin plaustrum "farm cart", plōstrum, plōstellum "cart", and plōxenum, plōximum "cart box".[6] [7] The give-and-take must take originally referred to the wheeled heavy plough, common in Roman northward-western Europe by the 5th century AD.[eight]

Many view plough every bit a derivative of the verb *plehan ~ *plegan 'to accept responsibility' (cf. High german pflegen 'to look afterward, nurse'), which would explain, for instance, Old High German pfluog with its double meaning of 'plow' and 'livelihood'.[9] [10] [11] Guus Kroonen (2013)[12] proposes a vṛddhi-derivative of *plag/kkōn 'sod' (cf. Dutch plag 'sod', Old Norse plagg 'fabric', Middle High German pflacke 'rag, patch, stain'). Finally, Vladimir Orel (2003)[13] tentatively attaches plough to a PIE stem * blōkó- , which supposedly gave Old Armenian peɫem "to dig" and Welsh bwlch "crack", though the word may not exist of Indo-European origin.[ citation needed ]

Parts [edit]

The basic parts of the mod plough are:

- beam

- hitch (British English: hake)

- vertical regulator

- coulter (knife coulter pictured, but disk coulter common)

- chisel (foreshare)

- share (mainshare)

- mouldboard

Other parts include the frog (or frame), runner, landside, shin, trashboard, and stilts (handles).

On modern ploughs and some older ploughs, the mould board is divide from the share and runner, then these parts can be replaced without replacing the mould board. Chafe eventually wears out all parts of a plough that come into contact with the soil.

History [edit]

13th century delineation of a ploughing peasant, Royal Library of Spain

Hoeing [edit]

When agriculture was start developed, soil was turned using simple hand-held earthworks sticks and hoes.[4] These were used in highly fertile areas, such as the banks of the Nile, where the almanac overflowing rejuvenates the soil, to create drills (furrows) in which to establish seeds. Digging sticks, hoes and mattocks were not invented in whatsoever 1 place, and hoe cultivation must accept been common everywhere agronomics was practised. Hoe-farming is the traditional tillage method in tropical or sub-tropical regions, which are marked by stony soils, steep slope gradients, predominant root crops, and coarse grains grown at wide distances apart. While hoe-agriculture is all-time suited to these regions, it is used in some fashion everywhere. Instead of hoeing, some cultures use pigs to trample the soil and grub the earth.[ citation needed ]

Ard [edit]

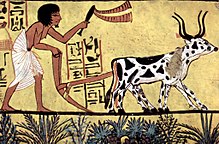

Ancient Egyptian ard, c. 1200 BC. (Burying chamber of Sennedjem)

Some ancient hoes, similar the Egyptian mr, were pointed and strong enough to clear rocky soil and make seed drills, which is why they are called hand-ards. However, domestication of oxen in Mesopotamia and the Indus valley civilization, mayhap equally early as the 6th millennium BC, provided mankind with the draft ability needed to develop the larger, creature-drawn true ard (or scratch plough). The earliest surviving evidence of ploughing has been dated to 3500–3800 BCE, on a site in Bubeneč, Czechia.[14] A ploughed field, from c.2800 BCE, was also discovered at Kalibangan, India.[15] A terracotta model of the early ards was found at Banawali, India, giving insight into the form of the tool used.[16] The ard remained like shooting fish in a barrel to replace if it became damaged and easy to replicate.[17]

The primeval was the bow ard, which consists of a typhoon-pole (or beam) pierced by a thinner vertical pointed stick called the caput (or body), with one cease beingness the stilt (handle) and the other a share (cutting blade) dragged through the topsoil to cut a shallow furrow suitable for most cereal crops. The ard does not clear new state well, and then hoes or mattocks had to exist used to pull upward grass and undergrowth, and a manus-held, coulter-like ristle could be fabricated to cut deeper furrows alee of the share. Because the ard left a strip of undisturbed earth betwixt furrows, the fields were oftentimes cross-ploughed lengthwise and breadth-wise, which tended to form squarish Celtic fields.[xviii] : 42 The ard is best suited to loamy or sandy soils that are naturally fertilised by annual flooding, as in the Nile Delta and Fertile Crescent, and to a lesser extent whatever other cereal-growing region with light or sparse soil. By the late Iron Historic period, ards in Europe were commonly fitted with coulters.[ commendation needed ]

Mould-board plough [edit]

A reconstruction of a mouldboard plow

To grow crops regularly in less-fertile areas, information technology was once believed that the soil must exist turned to bring nutrients to the surface. A major accelerate for this type of farming was the turn plough, also known as the mould-board plough (UK), moldboard turn (United states), or frame-plough. A coulter (or skeith) could exist added to cut vertically into the ground merely ahead of the share (in front of the frog), a wedge-shaped cutting edge at the bottom forepart of the mould lath with the landside of the frame supporting the nether-share (below-basis component). The mould-board plough introduced in the 18th century was a major advance in technology.[four]

Chinese ploughs from Han times on fulfil all these conditions of efficiency nicely, which is presumably why the standard Han turn squad consisted of two animals only, and later teams usually of a single beast, rather than the 4, six or 8 draught animals common in Europe earlier the introduction of the curved mould-board and other new principles of pattern in the + 18th century. Though the mould-board plough first appeared in Europe in early medieval, if not in belatedly Roman, times, pre-eighteenth century mould-boards were usually wooden and direct (Fig. 59). The enormous labour involved in pulling such a clumsy construction necessitated large plough-teams, and this meant that big areas of land had to be reserved as pasture. In China, where much less creature power was required, it was not necessary to maintain the mixed arable-pasture economy typical of Europe: fallows could be reduced and the abundant area expanded, and a considerably larger population could be supported than on the same amount of land in Europe.[19]

—Francesca Bray

The upper parts of the frame carry (from the forepart) the coupling for the motive power (horses), the coulter and the landside frame. Depending on the size of the implement, and the number of furrows it is designed to plow at once, a fore-carriage with a wheel or wheels (known as a furrow wheel and support bike) may be added to support the frame (wheeled plow). In the case of a single-furrow plough in that location is 1 cycle at the front and handles at the rear for the ploughman to steer and maneuver it.[ citation needed ]

When dragged through a field, the coulter cuts down into the soil and the share cuts horizontally from the previous furrow to the vertical cutting. This releases a rectangular strip of sod to be lifted by the share and carried by the mould lath up and over, and so that the strip of sod (slice of the topsoil) that is being cut lifts and rolls over every bit the turn moves forward, dropping back upside down into the furrow and onto the turned soil from the previous run down the field. Each gap in the ground where the soil has been lifted and moved across (commonly to the correct) is called a furrow. The sod lifted from information technology rests at an angle of most 45 degrees in the next furrow, up the dorsum of the sod from the previous run.[ commendation needed ]

A series of ploughings run down a field leaves a row of sods partly in the furrows and partly on the ground lifted earlier. Visually, across the rows, at that place is the land on the left, a furrow (half the width of the removed strip of soil) and the removed strip near upside-down lying on about one-half of the previous strip of inverted soil, and so on across the field. Each layer of soil and the gutter information technology came from forms a classic furrow.

The mould-lath plough greatly reduced the fourth dimension needed to prepare a field and and then allowed a farmer to work a larger surface area of land. In addition, the resulting blueprint of low (under the mould lath) and loftier (abreast it) ridges in the soil forms water channels, allowing the soil to drain. In areas where snow build-upward causes difficulties, this lets farmers plant the soil earlier, as the snow run-off drains away more quickly.[ commendation needed ]

In that location are five major parts of a mouldboard plough:

- Mouldboard

- Share

- Landside (brusque or long)

- Frog (sometimes called a standard)

- Tailpiece

The share, landside and mould board are bolted to the frog, which is an irregular piece of cast iron at the base of operations of the plough body, to which the soil-wearing parts are bolted.[ commendation needed ]

The share is the edge that makes the horizontal cut to dissever the furrow piece from the soil below. Conventional shares are shaped to penetrate soil efficiently: the tip is pointed downward to pull the share into the ground to a regular depth. The clearance, usually referred to as suction or downwardly suction, varies with different makes and types of plough. Share configuration is related to soil type, especially in the downwards suction or concavity of its lower surface. More often than not 3 degrees of clearance or downwards suction are recognised: regular for light soil, deep for ordinary dry out soil, and double-deep for clay and gravelly soils.[ citation needed ]

As the share wears away, it becomes blunt and the plough will crave more power to pull it through the soil. A plough body with a worn share will not have enough "suck" to ensure it delves the basis to its full working depth.

In improver, the share has horizontal suction related to the amount its point is bent out of line with the land side. Down suction causes the plough to penetrate to proper depth when pulled forward, while horizontal suction causes the turn to create the desired width of furrow. The share is a plane part with a trapezoidal shape. It cuts the soil horizontally and lifts it. Mutual types are regular, winged-plane, bar-signal, and share with mounted or welded indicate. The regular share conserves a expert cut but is recommended on rock-gratis soils. The winged-plane share is used on heavy soil with a moderate amount of stones. The bar-point share can be used in extreme conditions (hard and stony soils). The share with a mounted point is somewhere between the last two types. Makers accept designed shares of various shapes (trapesium, diamond, etc.) with bolted point and wings, oft separately renewable. Sometimes the share-cutting edge is placed well in accelerate of the mould board to reduce the pulverizing activity of the soil.[ citation needed ]

The mould board is the part of the plow that receives the furrow slice from the share.[4] It is responsible for lifting and turning the furrow slice and sometimes for shattering it, depending on the type of mould board, ploughing depth and soil conditions. The intensity of this depends on the blazon of mould lath. To adapt dissimilar soil atmospheric condition and crop requirements, mould boards have been designed in unlike shapes, each producing its own furrow profile and surface finish, but essentially they still conform to the original plough body classification. The various types take been traditionally classified as general purpose, digger, and semi-digger, as described below.[ citation needed ]

Farmer ploughing with two horses, 1890s

- The general-purpose mould lath. This has a low draft body with a gentle, cantankerous-sectional convex curve from summit to bottom, which turns a furrow three parts wide past ii parts deep, e. g. 300 mm (12 in) broad past 200 mm (seven.9 in) deep. It turns the furrow slice slowly almost without breaking it, and is normally used for shallow ploughing (maximum 200 mm (vii.ix in) depth). It is useful for grassland ploughing and sets up the country for weathering by wintertime frosts, which reduces the time taken to set up a seedbed for spring sown crops.[ commendation needed ]

- The digger mould board is brusk, abruptly curved with a concave cross-section both from top to bottom and from shin to tail. It turns the furrow slice chop-chop, giving maximum shatter, deeper than its width. It is unremarkably used for very deep ploughing (300 mm (12 in) deep or more). It has a higher power requirement and leaves a very broken surface. Digger ploughs are mainly used for land for potatoes and other root crops.[ citation needed ]

- The semi-digger mould lath is somewhat shorter than the full general-purpose mould board, but with a concave cross-section and a more abrupt bend. Existence intermediate between the two mould boards described above, it has a performance that comes in between (approximately 250 mm (9.viii in) deep), with less shattering than the digger mouldboard. Information technology turns an almost square-sectioned furrow and leaves a more broken surface finish. Semi-digger mould boards tin can be used at diverse depths and speeds, which suits them for most of the full general ploughing on a farm.[ commendation needed ]

- In add-on, slatted mould boards are preferred by some farmers, though they are a less mutual type. They consist of a number of curved steel slats bolted to the frog along the length of the mould board, with gaps betwixt the slats. They tend to interruption up the soil more than than a full mould board and better soil movement beyond the mould lath when working in sticky soils where a solid mould lath does not scour well.[ citation needed ]

The land side is the flat plate which presses against and transmits the lateral thrust of the plow bottom to the furrow wall. Information technology helps to resist the side pressure exerted by the furrow slice on the mould board. Information technology as well helps to stabilise the plough while in functioning. The rear bottom end of the landslide, which rubs against the furrow sole, is known equally the heel. A heel iron is bolted to the end of the rear of the land side and helps to back up the back of the plough. The land side and share are arranged to give a "lead" towards the unploughed land, so helping to sustain the correct furrow width. The land side is ordinarily made of solid medium-carbon steel and is very short, except at the rear bottom of the turn. The heel or rear end of the rear land side may be subject to excessive wear if the rear wheel is out of aligning, and and so a chilled iron heel piece is frequently used. This is inexpensive and can be easily replaced. The land side is fastened to the frog by plough bolts.[ citation needed ]

The frog (standard) is the key part of the plough lesser to which the other components of the bottom are attached. It is an irregular slice of metal, which may be fabricated of cast fe for cast atomic number 26 ploughs or welded steel for steel ploughs. The frog is the foundation of the plough bottom. It takes the shock resulting from hitting rocks, and therefore should exist tough and potent. The frog is in plow fastened to the turn frame.[ citation needed ]

A runner extending from behind the share to the rear of the plough controls the direction of the plough, considering it is held against the bottom land-side corner of the new furrow being formed. The holding forcefulness is the weight of the sod, every bit it is raised and rotated, on the curved surface of the mould board. Because of this runner, the mould board plough is harder to turn effectually than the scratch plow, and its introduction brought nigh a change in the shape of fields – from mostly square fields into longer rectangular "strips" (hence the introduction of the furlong).[ citation needed ]

An advance on the basic design was the iron ploughshare, a replaceable horizontal cutting surface mounted on the tip of the share. The earliest ploughs with a detachable and replaceable share engagement from around 1000 BC in the Ancient Near Eastward,[21] and the earliest iron ploughshares from virtually 500 BC in Mainland china.[22] Early on mould boards were wedges that sat inside the cutting formed by the coulter, turning over the soil to the side. The ploughshare spread the cut horizontally below the surface, so that when the mould board lifted information technology, a wider area of soil was turned over. Mould boards are known in Uk from the late 6th century onwards.[23]

The mould-board turn type is usually set by the method with which the turn is attached to the tractor and the way it is lifted and carried. The basic types are:

- Three bicycle trailing type – attached to the standard tractor describe bar and carried on its own three wheels[ citation needed ]

- Mounted or integra – most utilize a three-signal hitch and accept a rear wheel in utilise simply when ploughing. Some also have a gauge wheel to regulate maximum depth.[ citation needed ]

- Semi-mounted – used principally for larger ploughs. These accept a rear bicycle which commonly carries weight and side thrust when ploughing and sometimes the weight of the rear end of the plough when lifted. The front of the plough is carried on the tractor lower or draft links.[ citation needed ]

Plough bicycle [edit]

- The gauge wheel is an auxiliary wheel to maintain uniform depths of ploughing in various soil conditions. It is usually placed in a hanging position.[ citation needed ]

- The land wheel of the plough runs on the ploughed land.[ commendation needed ]

- The front or rear furrow wheel of the plough runs in the furrow.[ commendation needed ]

Turn protective devices [edit]

When a turn hits a rock or other solid obstruction, serious impairment may result unless the plough is equipped with some safety device. The harm may exist bent or cleaved shares, aptitude standards, beams or braces.[ commendation needed ]

The three basic types of rubber devices used on mould-board ploughs are a spring release device in the turn drawbar, a trip beam structure on each bottom, and an automatic reset design on each bottom.[ citation needed ]

The spring release was used in the past about universally on abaft-type ploughs with one to iii or 4 bottoms. It is not applied on larger ploughs. When an obstacle is encountered, the spring release mechanism in the hitch permits the turn to uncouple from the tractor. When a hydraulic elevator is used on the turn, the hydraulic hoses will also usually uncouple automatically when the plough uncouples. Most plough makers offering an automatic reset system for tough conditions or rocky soils. The re-set machinery allows each body to move rearward and up to laissez passer without impairment over obstacles such equally rocks subconscious below soil surface. A heavy leaf or coil-bound mechanism that holds the body in its working position under normal conditions resets the plough after the obstruction is passed.[ citation needed ]

Another type of automobile-reset mechanism uses an oil (hydraulic) and gas accumulator. Shock loads crusade the oil to shrink the gas. When the gas expands again, the leg returns to its working ploughing position after passing over the obstacle. The simplest machinery is a breaking (shear) bolt that needs replacement. Shear bolts that break when a plough body hits an obstruction are a cheaper overload protection device.[ commendation needed ]

Trip-axle ploughs are synthetic with a swivel point in the beam. This is usually located some distance in a higher place the acme of the plough bottom. The bottom is held in normal ploughing position by a spring-operated latch. When an obstacle is encountered, the entire lesser is released and hinges back and up to laissez passer over the obstruction. It is necessary to dorsum up the tractor and plough to reset the bottom. This construction is used to protect the individual bottoms. The automatic reset design has merely recently[ when? ] been introduced on US ploughs, only has been used extensively on European and Australian ploughs. Here the axle is hinged at a betoken almost above the point of the share. The bottom is held in the normal position by a set of springs or a hydraulic cylinder on each lesser.[ citation needed ]

When an obstruction is encountered, the plow bottom hinges back and up in such a way as to pass over the obstruction, without stopping the tractor and plough. The bottom automatically returns to normal ploughing position as soon equally the obstacle is passed, without any pause of forrad motion. The automatic reset design permits higher field efficiencies since stopping for stones is practically eliminated. Information technology too reduces costs for broken shares, beams and other parts. The fast resetting activeness helps produce a meliorate task of ploughing, as big areas of unploughed state are not left, as they are when lifting a turn over a rock.[ commendation needed ]

Loy ploughing [edit]

Manual loy ploughing was a form used on minor farms in Ireland where farmers could non beget more than, or on hilly basis that precluded horses.[24] It was used up until the 1960s in poorer state.[25] It suited the moist Irish climate, as the trenches formed by turning in the sods provided drainage. It allowed potatoes to be grown in bogs (peat swamps) and on otherwise unfarmed mountain slopes.[26] [27]

Heavy ploughs [edit]

Chinese iron plough with curved mouldboard, 1637

In the basic mould-board plough, the depth of cut is adjusted by lifting confronting the runner in the furrow, which limited the weight of the plough to what a ploughman could easily lift. This limited the construction to a small amount of wood (although metallic edges were possible). These ploughs were fairly fragile and unsuitable for the heavier soils of northern Europe. The introduction of wheels to replace the runner allowed the weight of the plough to increment, and in turn the employ of a larger mould-board faced in metal. These heavy ploughs led to greater food production and eventually a marked population increase, showtime effectually Advertisement k.[28]

Before the Han Dynasty (202 BC – AD 220), Chinese ploughs were made almost wholly of wood except for the iron bract of the ploughshare. These were V-shaped iron pieces mounted on wooden blades and handles.[29] By the Han menstruation the entire ploughshare was made of cast fe. These are the primeval known heavy, mould-board iron ploughs.[22] [thirty] Several advancements such as the three-shared plow, the turn-and-sow implement, and the harrow were developed subsequently. By the end of the Song dynasty in 1279, Chinese ploughs had reached a state of development that would non be seen in The netherlands until the 17th century.[29]

The Romans achieved a heavy-wheeled mould-board plough in the late 3rd and fourth century Advertizing, for which archaeological evidence appears, for instance, in Roman Great britain.[31] The Greek and Roman mould-boards were usually tied to the bottom of the shaft with bits of rope, which made them more frail than the Chinese ones, and iron mould-boards did not appear in Europe until the 10th century.[29] The first indisputable appearance after the Roman period is in a northern Italian document of 643.[18] : 50 Old words connected with the heavy plough and its use announced in Slavic, suggesting possible early apply in that region.[18] : 49ff General adoption of the carruca heavy plough in Europe seems to have accompanied adoption of the iii-field system in the later 8th and early on 9th centuries, leading to improved agronomical productivity per unit of land in northern Europe.[18] : 69–78 This was accompanied past larger fields, known variously as carucates, ploughlands, and plough gates.

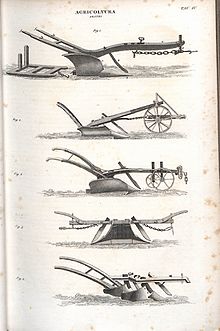

Improved designs [edit]

Mod tractor ploughing in South Africa. This plough has five non-reversible mouldboards. The fifth, empty furrow on the left may be filled by the first furrow of the next laissez passer.

'A Champion ploughman', from Australia, c. 1900

The basic plough with coulter, ploughshare and mould board remained in use for a millennium. Major changes in blueprint spread widely in the Age of Enlightenment, when there was rapid progress in design. Joseph Foljambe in Rotherham, England, in 1730, used new shapes based on the Rotherham plow, which covered the mould board with atomic number 26.[32] Unlike the heavy plough, the Rotherham, or Rotherham swing plough consisted entirely of the coulter, mould board and handles. Information technology was much lighter than earlier designs and became common in England. It may have been the starting time turn widely congenital in factories and commercially successful in that location.[33]

In 1789 Robert Ransome, an fe founder in Ipswich, started casting ploughshares in a disused malting at St Margaret's Ditches. A broken mould in his foundry caused molten metal to come into contact with cold metal, making the metal surface extremely difficult. This procedure, chilled casting, resulted in what Ransome advertised as "self-sharpening" ploughs. He received patents for his discovery.[ citation needed ]

James Small-scale further advanced the design. Using mathematical methods, he eventually arrived at a shape cast from a single piece of iron, an improvement on the Scots turn of James Anderson of Hermiston.[34] A unmarried-piece bandage-iron plough was also developed and patented by Charles Newbold in the United States. This was again improved on past Jethro Wood, a blacksmith of Scipio, New York, who fabricated a three-part Scots plough that allowed a broken slice to exist replaced. In 1837 John Deere introduced the first steel plough; it was so much stronger than iron designs that it could work soil in United states of america areas previously thought unsuitable for farming.

Improvements on this followed developments in metallurgy: steel coulters and shares with softer iron mould boards to prevent breakage, the chilled plough (an early example of surface-hardened steel),[35] and somewhen mould boards with faces strong enough to dispense with the coulter.[ citation needed ]

Unmarried-sided ploughing [edit]

Single-sided ploughing in a ploughing match

The get-go mould-board ploughs could only turn the soil over in 1 management (conventionally to the right), as dictated by the shape of the mould board; therefore, a field had to be ploughed in long strips, or lands. The plough was normally worked clockwise effectually each land, ploughing the long sides and beingness dragged beyond the short sides without ploughing. The length of the strip was limited by the altitude oxen (later horses) could comfortably work without rest, and their width by the distance the turn could conveniently exist dragged. These distances determined the traditional size of the strips: a furlong, (or "furrow's length", 220 yards (200 m)) past a concatenation (22 yards (20 m)) – an area of ane acre (about 0.4 hectares); this is the origin of the acre. The one-sided action gradually moved soil from the sides to the centre line of the strip. If the strip was in the same place each year, the soil built upwardly into a ridge, creating the ridge and furrow topography still seen in some ancient fields.[ citation needed ]

Turn-wrest plough [edit]

The turn-wrest plough allows ploughing to be washed to either side. The mould board is removable, turning to the right for one furrow, then existence moved to the other side of the plough to turn to the left. (The coulter and ploughshare are fixed.) Thus adjacent furrows tin be ploughed in reverse directions, allowing ploughing to proceed continuously along the field and and so avoid the ridge–furrow topography.[ citation needed ]

Reversible plough [edit]

The reversible (or roll-over) turn has two mould-lath ploughs mounted back to back, one turning right, the other left. While i works the land, the other is borne upside-down in the air. At the terminate of each row the paired ploughs are turned over so that the other can exist used forth the next furrow, again working the field in a consequent management.[ citation needed ]

These ploughs date back to the days of the steam engine and the horse. In almost universal use on farms, they have right and left-handed mould boards, enabling them to work up and downwardly the same furrow. Reversible ploughs may either be mounted or semi-mounted and are heavier and more than expensive than right-handed models, but have the dandy advantage of leaving a level surface that facilitates seedbed preparation and harvesting. Very piffling marking out is necessary before ploughing tin can start; idle running on the headland is minimal compared with conventional ploughs.[ citation needed ]

Driving a tractor with furrow-side wheels in the furrow lesser provides the most efficient line of draught between tractor and plough. It is also easier to steer the tractor; driving with the front wheel against the furrow wall will keep the forepart furrow at the correct width. This is less satisfactory when using a tractor with wide front tyres. Although these make meliorate use of the tractor ability, the tyres may compact some of the last furrow piece turned on the previous run. The problem is overcome by using a furrow widener or longer mould board on the rear body. The latter moves the soil further towards the ploughed land, leaving more room for the tractor wheels on the adjacent run.[ commendation needed ]

Driving with all four wheels on unploughed land is some other solution to the problem of broad tyres. Semi-mounted ploughs can be hitched in a way that allows the tractor to run on unbroken state and pull the plough in correct alignment without any sideways motion (crabbing).[ citation needed ]

Riding and multiple-furrow ploughs [edit]

Early tractor-drawn ii-furrow plow.

Early steel ploughs were walking ploughs, directed past a ploughman holding handles on either side of the plough. Steel ploughs were so much easier to depict through the soil that constant adjustment of the blade to deal with roots or clods was no longer necessary, every bit the plough could hands cut through them. Non long after that the kickoff riding ploughs appeared, whose wheels kept the plough at an adaptable level above the ground, while the ploughman sat on a seat instead of walking. Direction was now controlled generally through the draught team, with levers allowing fine adjustments. This led quickly to riding ploughs with multiple mould boards, which dramatically increased ploughing performance.[ citation needed ]

A single draught horse can normally pull a single-furrow turn in clean calorie-free soil, only in heavier soils ii horses are needed, 1 walking on the land and one in the furrow. Ploughs with 2 or more furrows call for more than two horses, and unremarkably 1 or more than have to walk on the ploughed sod, which is hard going for them and means they tread newly ploughed state downwards. Information technology is usual to rest such horses every one-half-hour for about x minutes.[ citation needed ]

Improving metallurgy and blueprint [edit]

John Deere, an Illinois blacksmith, noted that ploughing many sticky, non-sandy soils might benefit from modifications in the design of the mould lath and the metals used. A polished needle would enter leather and fabric with greater ease and a polished pitchfork also require less endeavor. Looking for a polished, slicker surface for a plough, he experimented with portions of saw blades, and past 1837 was making polished, bandage steel ploughs. The free energy required was lessened, which enabled the utilise of larger ploughs and more constructive use of horse power.[ commendation needed ]

Balance plough [edit]

The advent of the mobile steam engine allowed steam power to exist practical to ploughing from about 1850. In Europe, soil weather condition were often too soft to support the weight of a traction engine. Instead, counterbalanced, wheeled ploughs, known as residue ploughs, were drawn by cables across the fields past pairs of ploughing engines on reverse field edges, or by a single engine cartoon directly towards it at ane end and drawing away from it via a pulley at the other. The balance plough had two sets of facing ploughs arranged then that when i was in the ground, the other was lifted in the air. When pulled in ane direction, the trailing ploughs were lowered onto the footing by the tension on the cable. When the plough reached the edge of the field, the other engine pulled the contrary cable, and the plow tilted (balanced), putting the other prepare of shares into the ground, and the plough worked back across the field.[ citation needed ]

A German Kemna balance turn. The left-turning set of shares have just completed a pass, and the right-turning shares are about to enter the ground to return across the field.

One set of ploughs was right-handed and the other left-handed, allowing continuous ploughing forth the field, as with the turn-wrest and reversible ploughs. The man credited with inventing the ploughing engine and associated residuum plough in the mid-19th century was John Fowler, an English agricultural engineer and inventor.[36] 1 notable producer of steam-powered ploughs was J.Kemna of Eastern Prussia, who became the "leading steam plow company on the European continent and penetrated the monopoly of English language companies on the world market"[37] at the beginning of the 20th century.[ citation needed ]

In America the firm soil of the Plains allowed direct pulling with steam tractors, such as the big Case, Reeves or Sawyer-Massey breaking engines. Gang ploughs of upwardly to 14 bottoms were used. Often these were used in regiments of engines, so that in a single field at that place might exist 10 steam tractors each drawing a plough. In this style hundreds of acres could be turned over in a mean solar day. But steam engines had the power to describe the big units. When internal combustion engines appeared, they lacked the comparable strength and ruggedness. Simply by reducing the number of shares could the work be completed.[ commendation needed ]

Stump-jump plough [edit]

The stump-leap plough, an Australian invention of the 1870s, is designed to break up new farming land that contains tree stumps and rocks expensive to remove. It uses a moveable weight to hold the ploughshare in position. When a tree stump or rock is encountered, the ploughshare is thrown up clear of the obstacle, to avoid breaking its harness or linkage. Ploughing can continue when the weight is returned to the earth.[ commendation needed ]

A simpler, later system uses a concave disc (or pair of them) gear up at a broad angle to the management of progress, using a concave shape to agree the disc into the soil – unless something hard strikes the circumference of the disc, causing information technology to roll upwardly and over the obstruction. As this is dragged forrad, the abrupt border of the disc cuts the soil, and the concave surface of the rotating disc lifts and throws the soil to the side. Information technology does non work likewise as a mould-lath turn (simply this is not seen as a drawback, because it helps to fight current of air erosion), but it does elevator and break upwards the soil (meet disc harrow).[ commendation needed ]

Mod ploughs [edit]

Modernistic ploughs are normally multiply reversible, mounted on a tractor with a iii-point linkage.[38] These commonly have from 2 to as many equally seven mould boards – and semi-mounted ploughs (whose lifting is assisted by a wheel about halfway along their length) tin accept as many as 18. The tractor'due south hydraulics are used to elevator and reverse the implement and to adjust furrow width and depth. The plougher still has to ready the draughting linkage from the tractor, so that the turn keeps the proper angle in the soil. This angle and depth can be controlled automatically by modern tractors. Equally a complement to the rear turn a two or three mould-board plough tin can be mounted on the front of the tractor if it is equipped with front three-point linkage.[ citation needed ]

Specialist ploughs [edit]

Chisel plough [edit]

The chisel plow is a mutual tool for deep cultivation (prepared land) with limited soil disruption. Its main function is to loosen and aerate the soils, while leaving crop residue on top. This plough tin can be used to reduce the effects of soil compaction and to help intermission upwardly ploughpan and hardpan. Dissimilar many other ploughs, the chisel will not invert or turn the soil. This feature has fabricated it a useful addition to no-till and low-till farming practices that effort to maximise the erosion-preventing benefits of keeping organic matter and farming residues present on the soil surface throughout the year. Thus the chisel plough is considered by some[ who? ] to exist more than sustainable than other types of turn, such as the mould-board plough.

A modern John Deere 8110 Subcontract Tractor using a chisel plough. The ploughing tines are at the rear, the decline-cutting coulters at the front end.

Bigham Blood brother Tomato Tiller

Chisel ploughs are condign more pop as a primary tillage tool in row-crop farming areas. Basically the chisel plow is a heavy-duty field cultivator intended to operate at depths from 15 cm (5.9 in) to as much equally 46 cm (18 in). However some models may run much deeper.[ clarification needed ] Each individual plough or shank is typically set from 230 mm (9 in) to 360 mm (14 in) apart. Such a plough can see pregnant soil drag: a tractor of sufficient power and traction is required. When ploughing with a chisel plough, 10–20 horsepower (seven.5–14.ix kW) per shank is required, depending on depth.[ commendation needed ]

Pull-blazon chisel ploughs are made in working widths from about 2.5 metres (eight ft 2 in) up to 13.vii metres (45 ft). They are tractor-mounted, and working depth is hydraulically controlled. Those more than about 4 metres (13 ft) broad may be equipped with folding wings to reduce transport width. Wider machines may have the wings supported by individual wheels and hinge joints to allow flexing of the auto over uneven ground. The wider models usually have a bicycle each side to control working depth. Iii-signal hitch-mounted units are fabricated in widths from virtually i.5 to 9 metres (4 ft 11 in to 29 ft half dozen in).

Cultivators are often like in form to chisel ploughs, simply their goals are different. Cultivator teeth piece of work about the surface, usually for weed control, whereas chisel plow shanks work deep under the surface; therefore, cultivation takes much less power per shank than does chisel ploughing.

Country plough [edit]

The land plough is a slanted plow.[39] The most mutual plough in India,[twoscore] it is recommended for crops like groundnut after the utilize of a tractor.[41]

Ridging plough [edit]

A ridging plough is used for crops such as potatoes or scallions grown buried in ridges of soil, using a technique chosen ridging or hilling. A ridging turn has two back-to-back mould boards cutting a deep furrow on each pass with loftier ridges either side. The same plough may be used to carve up the ridges to harvest the crop.

Scots hand plough [edit]

This variety of ridge plough is notable for having a bract pointing towards the operator. It is used solely by human effort rather than with brute or machine assist and pulled backwards past the operator, requiring great concrete endeavour. Information technology is specially used for 2nd breaking of ground and for white potato planting. It is found in Shetland, some western crofts, and more rarely Central Scotland, typically on holdings too modest or poor to merit the use of animals.

Mole plough [edit]

The mole plough allows under-drainage to be installed without trenches, or breaks up the deep impermeable soil layers that impede it. It is a deep plough with a torpedo or wedge-shaped tip and a narrow blade connecting it to the body. When dragged over footing, it leaves a channel deep under information technology that acts as a drain. Modern mole ploughs may besides bury a flexible perforated plastic drain pipe as they go, making a more permanent drain – or may be used to lay pipes for h2o supply or other purposes. Like machines, so-called pipe-and-cable-laying ploughs, are even used under the sea for laying cables or for preparing the world for side-browse sonar in a process used in oil exploration.

Compacting a tennis ball-sized sample from moling depth by hand, then pushing a pencil through is a uncomplicated check to discover if the subsoil is in the correct status for mole ploughing. If the hole stays intact without splitting the ball, the soil is in platonic condition for the mole plough.

Heavy land requires draining to reduce its h2o content to a level efficient for plant growth. Heavy soils commonly have a system of permanent drains, using perforated plastic or dirt pipes that discharge into a ditch. The small tunnels (mole drains) that mole ploughs form prevarication at a depth of up to 950 mm (37 in) at an angle to the pipe drains. Water from the mole drains seeps into the pipes and runs forth them into a ditch.

Mole ploughs are usually trailed and pulled past a crawler tractor, but lighter models for utilize on the 3-point linkage of powerful four-bicycle drive tractors are too made. A mole turn has a potent frame that slides along the footing when the machine is at piece of work. A heavy leg, like to a sub-soiler leg, is fastened to the frame and a circular section with a larger diameter expander on a flexible link is bolted to the leg. The bullet-shaped share forms a tunnel in the soil about 75 mm (3.0 in) diameter and the expander presses the soil outwards to grade a long-lasting drainage channel.

Para-plough [edit]

The para-plow, or paraplow, loosens compacted soil layers iii to 4 dm (12 to 16 inches) deep while maintaining high surface remainder levels.[42] It is primary cultivation implement for deep ploughing without inversion.

Spade plough [edit]

The spade plough is designed to cut the soil and plough it on its side, minimising impairment to earthworms, soil microorganism and fungi. This increases the sustainability and long-term fertility of the soil.

Switch plough [edit]

Using a bar with square shares mounted perpendicularly and a pivot betoken to change the bar's angle, the switch turn allows ploughing in either management. It is best in previously-worked soils, as the ploughshares are designed more to turn the soil over than for deep tillage. At the headland, the operator pivots the bar (and and so the ploughshares) to turn the soil to the reverse side of the direction of travel. Switch ploughs are usually lighter than curl-over ploughs, requiring less horsepower to operate.

Furnishings of mould-board ploughing [edit]

Mould-board ploughing in cold and temperate climates, down to 20 cm (seven.nine in), aerates the soil by loosening information technology. It incorporates crop residues, solid manures, limestone and commercial fertilisers aslope oxygen, and then reducing nitrogen losses by denitrification, accelerating mineralisation and raising short-term nitrogen availability for turning organic matter into humus. It erases wheel tracks and ruts from harvesting equipment. Information technology controls many perennial weeds and delays the growth of others until leap. It accelerates leap soil warming and water evaporation due to lower residues on the soil surface. It facilitates seeding with a lighter seed, controls many crop enemies (slugs, crane flies, seedcorn maggots-bean seed flies, borers), and raises the number of "soil-eating" earthworms (endogic), but deters vertical-abode earthworms (anecic).[ citation needed ]

Ploughing leaves trivial crop residue on the surface that might otherwise reduce both current of air and water erosion. Over-ploughing tin atomic number 82 to the formation of hardpan. Typically, farmers break that up with a subsoiler, which acts as a long, sharp pocketknife slicing through the hardened layer of soil deep below the surface. Soil erosion due to improper land and plough utilisation is possible. Profile ploughing mitigates soil erosion by ploughing across a slope, forth elevation lines. Alternatives to ploughing, such as a no-till method, accept the potential to build soil levels and humus. These may be suitable for smaller, intensively cultivated plots and for farming on poor, shallow or degraded soils that ploughing would further dethrone.[ commendation needed ]

Depictions [edit]

- Ploughs in fine art

-

Back side of a 100 mark banknote issued 1908

-

-

-

-

-

-

Plough-usage was revolutionized with the appearance of steam-locomotives (as seen in this High german 1890s watercolor)

-

-

Plough pictured in the coat of arms of Aura

-

Run into also [edit]

- Boustrophedon (Greek: "ox-turning") — an ancient way of writing, each line existence read in the contrary direction like reversible ploughing.

- Conduit current collection

- Foot plough

- Headland (agronomics)

- History of agriculture

- Railroad turn

- Ransome Victory Plough

- Silviculture has a technique for preparing soil for seeding in forests called scarification, which is explained in that article.

- Snowplough

- Whippletree

References [edit]

- ^ "Turn". Cambridge English Dictionary . Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ^ "BBC - Anglo-Saxon 7th Century plough coulter found in Kent - 7 April 2022". BBC News. 7 Apr 2022.

- ^ Collingwood, R. G.; Collingwood, Robin George; Nowell, John; Myres, Linton (1936). Roman Britain and the English Settlements. Biblo & Tannen Publishers. p. 211. ISBN9780819611604.

- ^ a b c d "Plow". Encyclopaedia Britannica . Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ^ Sahgal, A C; Sahgal, Mukul. Living Sci. viii Argent Jubilee. Republic of india: Ratna Sagar. p. 7. ISBN9788183325035.

- ^ C. T. Onions, ed., Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology, s.v. "plow" (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996).

- ^ Webster'due south Encyclopedic Unabridged Dictionary of the English, s.5. "plough" (NY: Gramercy Books, 1996).

- ^ Weller, Dr. Judith A. (1999). "Agricultural Use". Roman Traction Systems . Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ Jaan Puhvel, "The Indo-European and Indo-Aryan turn: a linguistic study of technological diffusion", Technology and Civilization v, no. 2 (1964): 176-90.

- ^ Jan de Vries, Nederlands Etymologisch Woordenboek, s.v. "ploeg" (Leiden: Brill, 1971).

- ^ Ruth Schmidt-Wiegand, 'Wörter und Sachen. Zur Bedeutung einer Methode für die Frühmittelalterforschung. Der Pflug und seine Bezeichnungen', in Wörter und Sachen im Lichte der Bezeichnungsforschung (Berlin: B.R.D.; NY: Walter de Gruyter, 1981), 1-41; Heinrich Beck, 'Zur Terminologie von Pflug und Pflügen - vornehmlich in den nordischen und kontinentalen germanischen Sprachen', in Untersuchungen zur eisenzeitlichen und frühmittelalterlichen Flur in Mitteleuropa und ihre Nutzung, eds. Heinrich Beck et al. (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1980), 2: 82-98.

- ^ Guus Kroonen, Etymological Lexicon of Proto-Germanic, s.v. "*plōga-" (Leiden: Brill, 2022), 398.

- ^ Vladimir Orel, A Handbook of Germanic Etymology, s.five. "*plōȝuz" (Leiden: Brill, 2003), 292.

- ^ "Found of Archeology of CAS report". Archived from the original on 29 August 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ Lal, BB (2003). Excavations at Kalibangan, the Early on Harappans, 1960–1969. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 17 and 98

- ^ McIntosh, Jane (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. p. 121. ISBN9781576079072.

- ^ "The Plow". Story of Farming.

- ^ a b c d Lynn White, Jr., Medieval Engineering science and Social Change (Oxford: University Printing, 1962)

- ^ Bray 1984, p. 178.

- ^ Jagor, Fedor (1873). Reisen in den Philippinen. Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung.

- ^ 1000. D. White (1984): Greek and Roman Engineering, London: Thames and Hudson, p. 59.

- ^ a b Robert Greenberger, The Technology of Ancient Mainland china (New York: Rosen Publishing Group, Inc., 2006), pp. xi–12.

- ^ Hill and Kucharski 1990.

- ^ Paul Hughes (iii March 2022). "Castlepollard venue to host Westmeath ploughing finals". Westmeath Examiner. Archived from the original on 2 October 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ Patrick Freyne (27 September 2009). "The plow and the stars". Sunday Tribune. Dublin. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ "The Famine Potato". St Mary's Famine History Museum. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ Jonathan Bell, "Wooden Ploughs From the Mountains of Mourne, Ireland", Tools & Tillage (1980) iv#1. pp. 46–56; Mervyn Watson, "Common Irish Plough Types and Cultivation Techniques", Tools & Cultivation (1985) 5#2. pp. 85–98.

- ^ Weber, William (2014). Production, Growth, and the Surround: An Economic Approach. CRC Press. p. 63. ISBN9781482243062.

- ^ a b c http://www.computersmiths.com/chineseinvention/ironplow.htm

- ^ Wang Zhongshu, trans. by Thousand. C. Chang etc., Han Civilization (New Oasis and London: Yale University Press, 1982).

- ^ Evi Margaritis and Martin K. Jones: "Greek and Roman Agriculture", Oleson, John Peter, ed.: The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical Earth, Oxford Academy Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-xix-518731-i, pp. 158–174 (166, 170).

- ^ "A Brief History of The Plow".

- ^ "The Rotherham Plough". rotherhamweb.co.uk. Archived from the original on 24 September 2022.

- ^ Wilson, Rick (2015). Scots Who Fabricated America. Birlinn. ISBN9780857908827.

- ^ "John Deere (1804–1886)".

- ^ Archives, The National. "The Discovery Service". discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk . Retrieved 26 September 2022.

Patent litigation [TR FOW/CO5/116-137] is mainly concerned with a Chancery case of 1863 between John Fowler and his patent assignees in trust against James and Frederick Howard of Bedford for alleged infringement of his patents by the manufacture of balance ploughs.

- ^ Biographie, Deutsche. "Kemna, Julius - Deutsche Biographie". world wide web.deutsche-biographie.de (in German language). Retrieved xviii July 2022.

- ^ Blanco-Canqui, Humberto; Lal, Rattan (2008). Principles of Soil Conservation and Management. Springer. p. 198. ISBN9781402087097.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). www.hillagric.ac.in. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 November 2022. Retrieved 11 Jan 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Fodder and Grass: Land plough".

- ^ "Agronomics :: Oil Seeds :: Groundnut". Archived from the original on 24 July 2022.

- ^ "Tillage Equipment" (PDF). Natural Resource Conservation Service. Retrieved 11 June 2022. [ permanent expressionless link ]

Farther reading [edit]

- Bray, Francesca (1984), Science and Civilization in Communist china 6

- Liam Brunt, "Mechanical Innovation in the Industrial Revolution: The Case of Plough Design". Economical History Review (2003) 56#three, pp. 444–477 JSTOR 3698571

- P. Hill and K. Kucharski, "Early Medieval Ploughing at Whithorn and the Chronology of Plow Pebbles", Transactions of the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society, Vol. LXV, 1990, pp 73–83

- V. Sankaran Nair, Nanchinadu: Straw of Rice and Plough Culture in the Ancient World

- Wainwright, Raymond P.; Wesley F. Buchele; Stephen J. Marley; William I. Baldwin (1983). "A Variable Arroyo-Angle Moldboard Plow". Transactions of the ASAE. 26 (2): 392–396. doi:10.13031/2013.33944.

- Steven Stoll, Larding the Lean Earth: Soil and Society in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Hill and Wang, 2002)

External links [edit]

| | Look up plow in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ploughs. |

- The Rotherham Plough — the commencement commercially successful iron plough

- History of the steel plough — every bit developed past John Deere in the United States

- Breast Ploughs and other antique hand farm tools Archived 24 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "Tractor Guide Saves Labor for the Farmer", Pop Mechanics, December 1934

How To Set Up A Conventional Plough,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plough

Posted by: austinsuresse.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How To Set Up A Conventional Plough"

Post a Comment